Standing, sweating in the hot Texas sun somewhere between Houston and Austin, I look out into the vast pasture next to the road. I can see miles and miles of open land, with the occasional tree and cows. A small bird is perched quietly on the power line. Approximately the size of robin, it has a hooked beak and large head. There is a black stripe that runs across its eyes and forehead, making it look like a masked bandit. Its appearance is striking: grey body, black and white wings, and a black tail with white stripes. Colloquially known as the “butcher bird,” the loggerhead shrike (Lanius ludovicianus) is a member of the predatory passerines and one of the most phenomenal birds.

The loggerhead shrike displays a remarkable and rather barbaric style of hunting. Unlike other birds of prey (like the hawk), the shrike does not actively forage. Instead, it sits and waits, perched high above the ground. When it locates its prey, it attacks and impales the poor animal on nearby thorns. Once secure, the shrike will tear off chunks to eat. Also, unlike other predatory birds, the loggerhead shrike does not have strong talons. For hawks and owls, talons are used for attacking, but more importantly, talons are used to anchor down prey. To compensate for a lack of strong talons, the shrike has learned to anchor its prey on thorns! To the shrike’s credit, though, it does have a disproportionately large head and a strong, hooked beak allowing it to attack larger animals than other birds of its size.

The shrike’s unique hunting style attracts attention from birders and researchers alike. How does the impaling behavior develop? Is it instinctual or learned? Susan Smith, at the University of Washington, has been studying this impaling behavior at the Columbia National Wildlife Refuge in Washington. She is interested in the ontogeny of the attack. After extensive observation of 5 nests, she reported that no adults made an effort to teach the impaling behavior to their offspring before the young left the nest at 16 days. Adults impaled their prey at the site of killing, and tore off pieces, which were brought back to the young. She compared the development of the impaling behavior between the offspring in the field and hand-reared birds in the lab. She notes that young shrikes go through a series of developmental stages before learning to impale effectively. The first stage, “dabbing,” is simply manipulating an object by the beak: turning it sideways and placing it back down. In the next stage, “dragging,” the bird drags the object toward itself. “Wedging” involves the bird dragging an object into a position in which the object is held in place. Finally, true “impaling” is accomplished when the bird uses thorns to hold the object (food) in place. Remarkably, the time it took the birds to reach these behavioral stages was similar in both the wild and captive shrikes. Smith concluded that the shrikes do not require any special experiences to learn the preliminary motor behaviors (ie, dragging), but need to learn to orient their food toward thorns for impaling.

One of the shrike’s keys to successful hunting is in using its powerful beak and strong bite to break the necks of small vertebrae. This allows the shrikes to attack and kill relatively large prey. Smith’s further research, using shrikes raised in the laboratory showed that by day 40, even inexperienced shrikes displayed the ability to attack the neck of small mouse-sized prey. Using stuffed mice as model prey, she observed the behavior of young shrikes when presented with the prey. All 28 of the study birds recognized and oriented toward their respective mouse. Only a fraction of birds attacked, but none lost attention. Interestingly enough, of the birds that did attack, some had never been exposed to the attacking behavior. From this, Smith suggests that shrikes have inborn abilities (visual, olfactory, etc) used to recognize and attack prey.

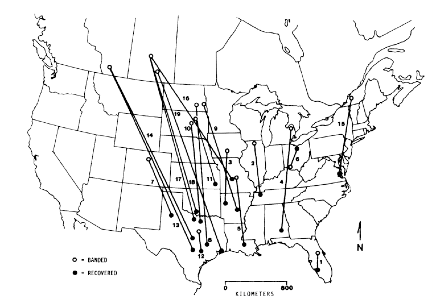

No matter where you go in the US, you can find loggerhead shrikes. Populations of shrikes can be found dispersed throughout the US and southern Canada. There are five main populations with wide breeding ranges. Rarely, do the breeding ranges overlap between populations. The shrikes’ movements from breeding grounds in the north to winter grounds in the south are not completely understood. Based on a compilation of banding data, Burnside confirmed that shrikes are partly migratory, with northern populations moving toward the southeastern US in the winter. Some shrikes are moving thousands of meters every winter. For example, shrikes banded in Saskatchewan were later found in Texas. That is a distance of over 2500 kilometers!

On my 3 hours drive from Austin to Houston, I only saw 3 shrikes. 50 years ago, however, the shrike population was burgeoning and I bet I would have seen many more. No one is sure exactly why the shrike has seen declining numbers, but much of the research on these birds has been driven by efforts to conserve the species. Special measures have been taken to understand and characterize the shrike’s breeding habitat, in hopes of maintaining the optimum environment for shrike breeding. Brooks and Temple at the University of Wisconsin thoroughly studied the habitat of shrikes in the upper Midwest. They found that shrikes primarily live in open, agricultural areas with grasslands. The shrike requires a relatively elevated perch site (average 2.3 m). Their research focused on 4 main aspects of the habitat, important to survival and breeding: herbaceous ground cover, potential and usable foraging habitat, and potential nesting sites. With these data, they developed sustainability indices to quantitatively assess an areas capacity to support the shrike.

Extreme measures are being taken in areas where the shrike population is especially low. In 1977, the San Clemente loggerhead shrike was listed as an endangered species. The population continued to decline as humans and feral goats habitually destroyed their breeding grounds. In 1991, only 14-20 adult of the population were left in US. A team of researchers in San Diego developed an artificial incubation and hand-rearing program in an effort to revive the population. The team had to take into account proper hatching conditions, diet, and re-introduction methods. The small, thin-shelled eggs must be kept in specific conditions. Without parental nurturing and care, the eggs have to be provided with a high-protein diet to allow for growth. Finally, the chicks must be able to survive back in the wild after being hand-reared. With a set of experimental diets, they tested their protocol on a non-endangered shrike population. They translated their research to the San Clemente population and were successfully able to rear 10 shrikes, which were released into the wild.

What a shame the loggerhead shrike population is declining so rapidly. It truly is an amazing bird. If its striking appearance wasn’t enough, it also has developed one of the most unique, yet successful, hunting techniques: attack and impale. I have yet to see this extraordinary behavior with my own eyes. However, I am going to pay much more attention to birds perched on tree branches and power lines. If I can find another perched loggerhead shrike, an attack is not far away. I just hope I am not the one the “butcher bird” is attacking!

References:

Smith SM. 1972. The Ontogeny of Impaling Behavior in the Loggerhead Shrike, Lanius ludovicianus L. Behavior 42: 232-247. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4533459

- This paper describes Smith’s study into the impaling behavior exhibited by young shrikes. She talks about the general hunting patterns of the Loggerhead shrike, its physical characteristics, and her observations in the field and in the lab.

Smith SM. 1973. A Study of Prey-attack Behavior in Young Loggerhead Shrikes, Lanius ludovicianus L. Behavior 44: 113-141. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4533483

- In this paper, Smith discusses her study of shrike attacks in the field and in the lab. She used models to elucidate how young shrikes attack prey.

Burnside, FL. 1987. Long-distance Movement by Loggerhead Shrikes. Journal of Field Ornithology 58: 62-65. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4513190

- This paper compiles previous studies of banding and recovery of loggerhead shrikes during winter migration. It also includes maps of migratory patterns and breeding regions.

Brooks, BL and Temple, SA. 1990. Habitat Availability and Suitability for Loggerhead Shrikes in the Upper Midwest. American Midland Naturalist 123: 75-83 http://www.jstor.org/stable/2425761

- In this paper, Brooks and Temple characterized the breeding region of the loggerhead shrike and created sustainability curves for conservation efforts.

Kuehler, CM, Mcilraith, B, Lieberman, A, Everett, W, Scott, TA, Morrison, ML & Winchell, C. 1993. Artificial incubation and hand-rearing of Loggerhead Shrikes. Wildlife Society Bulletin 21: 165-171. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3782919

- This paper describes the efforts taken by a team of zoologists to artificially incubate and hand-rear and endangered population of loggerhead shrikes.

Figure from Smith study on the ontogeny of shrike behavior (Smith, 1972). This graph shows the frequency of observed behaviors by captive (dashed) and wild (solid) shrikes as a function of age. The onset for these behaviors is remarkably similar even though the environments are different.

Figure from Burnside’s study of shrike movement (Burnside, 1987). The map depicts banding (open circle) and recovery (closed circle) sites for loggerhead shrikes that moved more than 100 km.Figure from Burnside’s study of shrike movement (Burnside, 1987). The map depicts the breeding zones for 5 populations of loggerhead shrikes: 1) L.l.ludovicianus, 2) L.l.migrans, 3) L.l.excubitorides, 4) L.l.nevadensis, 5) L.l.gambeli. Shaded areas are an overlap of breeding regions.

Figure from Burnside’s study of shrike movement (Burnside, 1987). The map depicts the breeding zones for 5 populations of loggerhead shrikes: 1) L.l.ludovicianus, 2) L.l.migrans, 3) L.l.excubitorides, 4) L.l.nevadensis, 5) L.l.gambeli. Shaded areas are an overlap of breeding regions.

Figure depicting suitability index curves for four elements on the loggerhead shrike breeding habitat: A) percent herbaceous ground cover in 25 ha land plot, B) percent potential foraging habitat in 25 ha land plot, C) percent usable foraging habitat in 25 ha land plot, D) number of potential nesting sites in .25 mile radius. (Brooks and Temple, 1990)

Can you tell me if the shrike is responsible for no other bird life coming into our garden? We have bird feeders, bird baths and a whole lot of indigenous plants, but no birds other than a solitary shrike and, occassionaly, his mate.

Shrikes generally eat smaller prey than birds, so I would be surprised if this were the case. Where are you located? Maybe it is not a time of year that brings birds to your garden. Feeders are more attractive in winter, for example.

5 years ago we had a loggerhead shrike on our property, startling all the birds. A Cardinal flew into our window and stunned itself. We did not know a shrike was in the area until it attacked the stunned bird. I ran out and had a problem getting the shrike to release the cardinal but once I did, it flew off and I revived the stunned bird and it flew away. I hadn’t seen a shrike in 50+ years and haven’t seen one since.

Shrikes are such fascinating birds. They hold their prey in their beaks since they can’t do it with talons. For my money, I would easily sacrifice a common cardinal for a lovely, uncommon shrike’s meal. But isn’t it fun to watch actual bird behavior in nature?

I love the shrikes, I wish we had more here in north texas!

Several weeks ago l saw what appeared to be a butcher bird nesting in an oak tree located in the rear parking lot of a Texas Roadhouse Grill in Orange City, Fl. I live in Orlando and had never seen one before. It caught my attention with its bold colors. It is a very attractive bird.